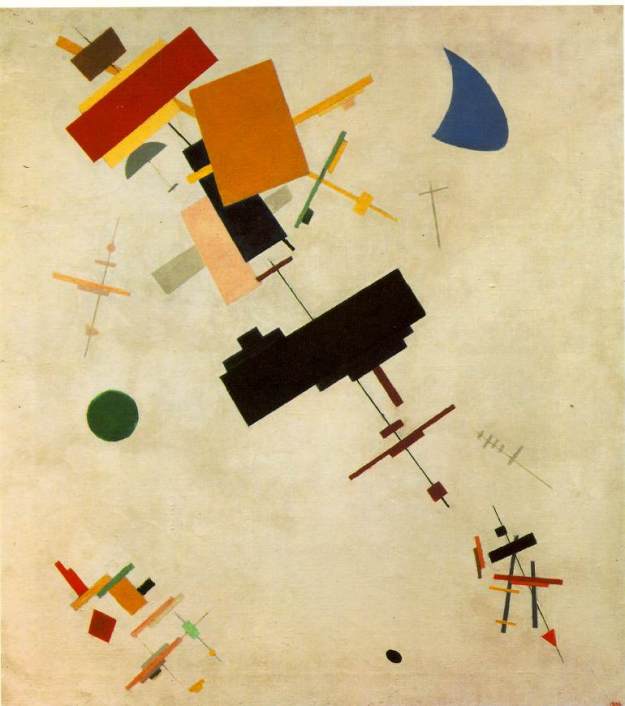

Bryan Wynter is one of my favourite abstract artists because his style is so raw and needs so little form to be so incredibly well structured and coherent. Wynter is one of the St. Ives British painters. He became addicted to mescaline, a powerful hallucinogenic drug, which is believed to have had a huge influence on his paintings. Much of his work was heavily inspired by nature.

Torrid Zone

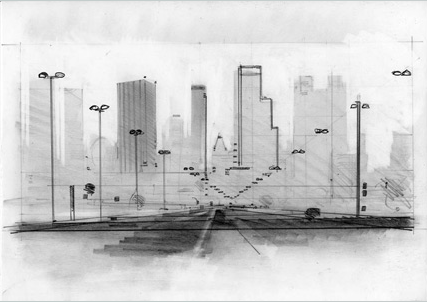

The painting above is one of my favourite paintings by Wynter and one of the first paintings I ever saw by him. The stacked nature of the shapes and strokes makes me think of a very diverse meadow with towering grasses. Certainly some of the more defined shapes could even be flowers. However, the painting is clearly more abstract than abstracted, I believe it heavily reflects nature as its main influence but is not necessarily meant to be of aspects of nature. One thing that really draws me to Wynter’s work is how, with so little definition and so much energy and activity, he manages to create a kind of structure to his paintings. The strokes are stacked with shapes and colours often following a pattern that tapers out through the painting or is overcome by another one. I think an interesting take would be to recreate this with buildings. The stacked uniformity of buildings from birds eye few would be interesting to use as an influence for this kind of style. Throughout the chaos he creates on the canvas, Wynter amazingly manages to produce a piece packed with themes, motifs and is amazingly coherent.

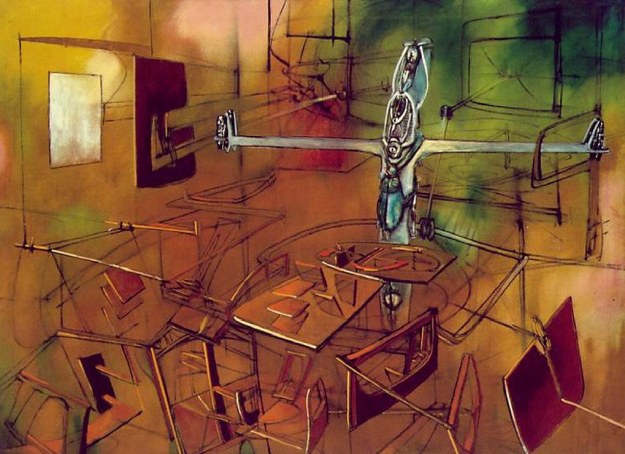

The comparison I’d like to make between Wynter and Matta comes as a result of the fact that Wynter maintains this structure and coherence throughout his chaos. In the painting below, Matta manages to create a kind of structure through his careful placement of lines of white over a beautifully chaotic background.

This scribbly style manages to be very different to Wynters while creating a similar effect. As chaotic as the image seems, it feels as though every piece of it was placed there with a purpose and it has a kind of coherence around the placement and integration of the white lines which form some slightly more defined shapes protruding from the background.

In terms of its colour scheme I find it to be more similar to two other paintings by Wynter:

Mineral World – Left, and Atavistic Group – Right.

Here it is obvious where the two differ quite significantly. While Wynter’s shapes tend to be stacked and arranged over the top of more shapes or textures, Matta’s tend to be drawn out of the less defined background with the introduction of lines and the smoothing or calming of the textures around these guiding lines.

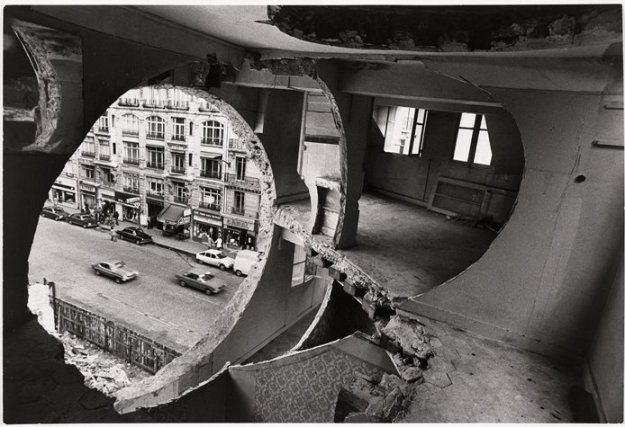

I love how, particularly in Mineral World, the square-ish forms could almost be small buildings or flowers or indeed the intricate and exciting textures on the side of a rock with minerals protruding. Again, despite it’s chaos it almost becomes very uniform. The stacking of shapes is similar to a feature of the painting shown below, by Matta:

This painting is much much less textured than either of the ones shown by Bryan Wynter however it does possess a similar colour scheme and this wonderful idea of order emerging from chaos or being the product of chaos.

My favourite painting by Bryan Wynter is Seawall, shown below. I love his use of he colours and how he keeps the dark blues very close to blacks. How, again, we see another example of curves being used to create motion. His scarce use of white in the centre and his preference of light blues to actual white when creating a contrast to the darkness creates this beautiful sense of the water flowing. As with most Bryan Wynter paintings, it is his textures which are most intriguing, in this case perfectly representing the glinting of light of the uneven surface of falling water.

Seawall

The use of shape and organisation forming or emerging from chaos is an idea I would like to explore in my final piece.